Just Tell Me What Cherry Tree I Need

For a dessert cherry i.e. eating, get a Lapins Cherokee, Celeste, Sweetheart, Sunburst, Stella or Summer Sun.

For a sour cherry i.e. cooking cherry tree, get a Morello. These have all received awards from the RHS and will produce fruit with no other cherry trees near by and give good results across the whole UK. If those are unavailable, get any that are self fertile. There are plenty of great reasons to buy a different cherry tree to those listed. Some have a richer taste, are more disease resistant, split less or you may need a pollination partner to increase fruit yields. Now it is worth while reading further.

Introduction

Cherry trees can be a very rewarding fruit tree in the UK, possibly because nailing wanted posters and lost pet flyers to them can yield financial fruit that is available all year round. They also offer seasonal beauty and delicious summer harvests.

In early spring, they put on a spectacular display of white or pink blossoms[1], so if you purchased an unknown cherry tree, then you can realistically expect “whink” coloured blossoms (White or Pink). Good job the colours were not SHell and whITE).

Both shades are not only beautiful but also provide an important early nectar source for pollinators[2] to suck up— unlike a Nectar card, which provides nothing but a headache no matter how much you suck on it.

By mid-to-late summer, these blooms turn into rich, glossy fruits ranging from succulent, sweet cherries for eating fresh, to sharp, flavourful sour types ideal for cooking, jams or preserves[3]. Unlike many other fruits, cherries ripen earlier, often by late June[4], meaning you’ll be snacking while the apples and pears are still growing.

Many modern cultivars are self-fertile[5], meaning they will produce fruit if planted on their own and have rootstock options to provide larger cherry trees to smaller pot-grown patio trees. Available in different shapes or forms to give different benefits, covered later in this article.

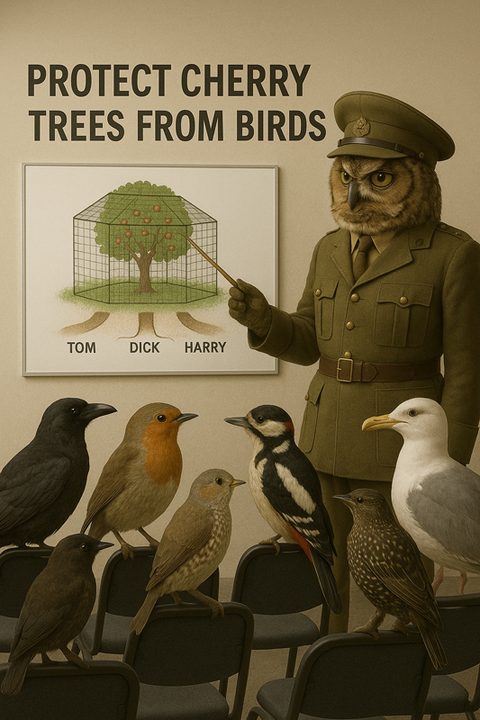

Considered to be low maintenance and suitable for most environments[6]. Cherry trees crop earlier than apples and pears, avoid the large crop/sucky crop cycle of plums[7], and provide a very generous and thoughtful food source for the birds[8] (a perspective most commonly found with gardeners who forgot or couldn’t be bothered to net their trees).

Growing Cherry Trees In The UK

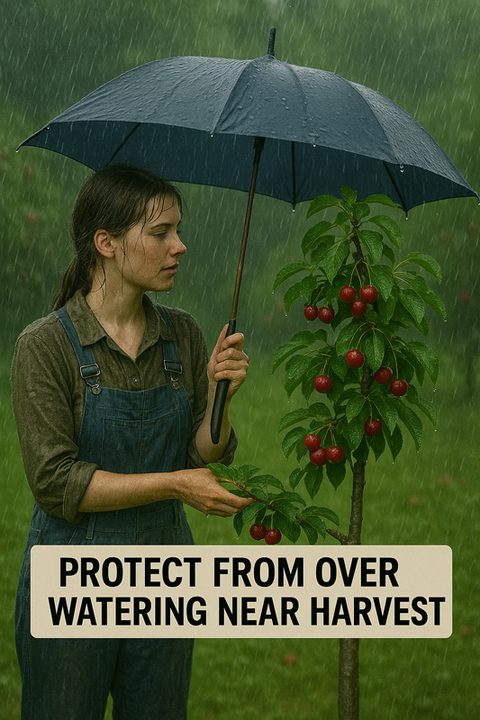

Cherry trees can be grown successfully across the UK, but the choice of variety and growing method makes a big difference. Dessert sweet cherries (Prunus avium) love warmth and shelter, so they perform best in southern and central England[3]. Gardeners further north — in Yorkshire, the North East, or into Scotland — can still grow sweet cherries, but the climate makes them more unpredictable. Shorter, cooler summers often mean smaller crops, and wet weather close to ripening increases the risk of fruit splitting[9]. Microclimates like sheltered courtyards and walled gardens can improve crop yields[10].

That doesn’t mean northern growers should give up on sweet cherries altogether. There are practical ways to tilt the odds in your favour. Training a tree as a fan against a sunny, south-facing wall captures extra heat and protects blossom from wind[10]. We mean fan shaped not teaching your tree to move air around.

Growing under a polytunnel, greenhouse, or rain shelter prevents excess moisture that leads to splitting and also warms the microclimate[11]. Choosing later-flowering, self-fertile cultivars such as ‘Stella’ or ‘Lapins’ helps avoid frost damage to blossom in cooler springs[12]. Consistent watering during dry spells, combined with good mulching, reduces stress and helps fruit ripen more evenly[3].

By contrast, sour cherries like the tough ‘Morello’ (Prunus cerasus) are reliable croppers almost anywhere in Britain[13]. They’ll tolerate partial shade and even thrive on a north-facing wall[10], making them one of the few fruit trees that actively suit tricky northern plots. With fertile, well-drained soil and some attention to site selection, gardeners right across the UK can grow cherries — but above the Midlands, a little protection and later flowering cherry trees make the difference between cherry-pick the best ones and cherry-pick the stressed ones.

Cherries do best in fertile, well-drained soils with a neutral to slightly acidic pH of around 6.5–6.7[14]. They dislike heavy clay or waterlogged ground, which can encourage bacterial canker and poor root growth[15], so improving drainage with organic matter or planting on a slight mound can make a big difference. While they’ll tolerate lighter sandy soils, these dry out quickly, so regular mulching is essential to conserve moisture[16]. In short, cherries are happiest in moisture-retentive but free-draining ground — the same balance most fruit trees prefer.

Choosing The Right Cherry Tree

Sweet vs Sour: Dessert Vs Cooking

Cherries fall into two main groups.

When ripe and about to fall, those facing the sun have a fatter and juicier side that makes them roll south after they hit the floor, while the others roll north i.e. creating two distinctive main groups after they have fallen. If you believe that, we have some magic beans for sale.

Sweet cherries are grown mainly for fresh eating, prized for their sugar content, juicy texture and larger fruit size, often in the 19–28 mm range[17]. Their glossy, firm flesh makes them ideal straight from the tree or in desserts with little added sugar.

Sour cherries, by contrast, average 15–20 mm[18]. Usually too tart to eat raw, they excel in bakes, preserves and drinks where their sharpness gives depth of flavour.

In the UK, sweet cherries crop from late June to July, with cultivars like ‘Celeste’ early and ‘Sweetheart’ extending into August[3]. Sour cherries ripen slightly later, July into early August, and because they flower later, they are more reliable in cooler or wetter regions[13].

Weather is critical. Sweet cherries often split after heavy rain near harvest[9]. Sour cherries resist cracking better and crop more consistently. Storage also differs: sweet cherries last only about seven days refrigerated[19], while sour cherries are usually processed immediately for freezing, canning or drying where they hold flavour well[20].

In the kitchen, sweet cherries need little sugar but can taste bland once baked, while sour cherries almost always require sweetening yet give a sharper, more intense flavour in pies and preserves[18]. Both provide vitamin C, potassium and fibre, but sour cherries have higher anthocyanins and melatonin, linked to reduced inflammation, faster recovery and better sleep[21].

In short, if you’re going to cherry-pick: sweet cherries win for fresh eating and looks, while sour cherries win for hardiness, reliability and culinary punch.

Pollination & Self-Fertile Cultivars

This is how a cherry tree “loses it’s cherry”.

There are three components required, an anther, stigma and pollen and a cherry tree flower has all three of these inside each flower. Pollen grown on the anther will fertilise the stigma and a fruit will grown. Cherry trees that can do this are called self-fertile. If the pollen does not fertilise the stigma then these are not self-fertile. These will require the pollen from a different species of cherry tree.

In cherries, as in many fruit trees, pollination is carried out mainly by insects such as bees, which move pollen between blossoms as they forage[22]. They work a bit like a fertility clinic in that they are busy bees working amongst the stigma.

Nurseries label trees with a pollination group (usually a number or letter) that marks a two-week flowering window. For best results, choose another tree from the same group, or one above or below, to guarantee flower opening overlap and successful pollination. Modern cultivars such as Stella, Lapins, and Sunburst are self-fertile, while older types like Van or Bing require pollination partners[5][23]. Most good tree retailers will list a cherry tree's fertility status.

Even self-fertile cherries, however, often crop more heavily when a second compatible tree is nearby. Cross-pollination by bees can increase crop size, so expert gardeners often plant more than one type of cherry tree if space allows[24]. For sour cherries like Morello, which are naturally self-fertile, yields are reliable even in isolation, but cross-pollination may still improve consistency[13].

For maximum effect, cherries should be planted within about 25 m of each other so that bees can move easily between them[25]. As with most prime real estate, positioning them in sunny, sheltered sites with good airflow encourages Air Bee and Bee stays along with other insect activity. Avoid spraying insecticides during blossoming to protect visiting bees. Where only one tree can be grown, choosing a self-fertile variety is best. In summary, a self-fertile cherry tree can “GO FERTILISE ITSELF!” whereas a non-self-fertile tree cannot; it needs a hand.

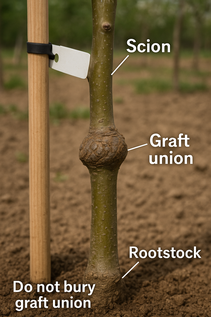

Rootstocks & Sizes

Cherry trees are like people, not in the way we can get fruity, throw shade, and creak when old but a mixture of two things coming together. Some people might call them “Frankenstrees,” but the industry calls them grafted. This is where you join or graft the roots of one tree onto a piece of another. The idea is to merge the benefits the roots offer with the benefits the fruiting part has to offer. A bit like merging capitalism with socialism — more benefits all round. The rootstock is the root system plus a small section of stem taken from another tree. It provides qualities such as strength, size control, soil adaptability, and disease resistance. Onto this, the scion is grafted — not Cylon, because we want cherries, not human-killing robots. The scion is the part that grows into the fruit-bearing section. You can usually spot the graft union as a slight bulge about 30 cm above ground. Everything above it is the scion, responsible for flavour, sweetness, and yield[26][27].

Rootstocks strongly influence tree vigour. A vigorous rootstock can produce a tree up to 10 m tall, while dwarfing and ultra-dwarfing rootstocks restrict growth to a much smaller size, between 2–4 m, perfect for small gardens or containers. Dwarfing also encourages earlier fruiting, meaning you’ll enjoy cherries much sooner than on a traditional orchard-sized tree[28][29].

Common cherry rootstocks in the UK include:

VVA-1 (Krymsk® 5): Ultra-compact, typically 2–2.5 m tall. Perfect for patios, containers, and fans, with very early cropping. Needs fertile soil, regular watering, and staking for support[30].

Gisela 5: A popular dwarfing rootstock, producing trees around 3–4 m. Excellent for small gardens and trained forms, though it benefits from staking and good feeding[31][31].

Colt: A semi-vigorous rootstock, giving mid-sized trees about 3.5–6 m. Tolerant of heavier soils and less demanding, making it popular for average UK gardens[31][32].

Mazzard / F12/1: A traditional vigorous rootstock, producing large trees of 6–10 m. Suited to orchards and parkland, but impractical for smaller plots[31][28]. Opting for vigorous rootstocks such as Mazzard or F12/1 may sound like a bold move, but it brings a whole new set of challenges. These trees can reach 6–10 m tall, which means pruning isn’t a quick job with a pair of secateurs — it’s a full-on operation. You’ll need tall ladders, long-reach saws or pruners, and ideally safety gear such as harnesses or scaffolding. Cuts on such large trees are thicker, slower to heal, and more prone to fungal infections, so every pruning decision carries extra risk. What’s manageable on Colt or Gisela 5 becomes an exercise in logistics on Mazzard or F12/1. For most gardeners, this scale of tree care is better left to professionals, unless you fancy turning cherry pruning into a high-altitude extreme sport.

Growing Cherry Trees From Seed

While most edible cherry trees in UK gardens are grafted onto rootstocks to achieve optimal results, it is possible to grow cherries from seed. Wild cherry (Prunus avium), often called “Gean”, naturally reproduces this way and has been raised from seed for centuries for timber, hedgerows, and ornamental planting[32]. If you ever wanted to sow the seed of doubt about cherry taste, try a Prunus avium cherry, you might think the bark tasted better.

Seed-grown cherries are genetically variable. A tree raised from a cherry stone may not resemble its parent in fruit quality or size — and in many cases the fruit is smaller, less sweet, or even poor for eating. This is because cherries are cross-pollinated, so the seed carries mixed genetics[18]. For this reason, commercial and garden fruiting cherries are almost always grafted rather than seed-grown so you can literally benefit from someone else’s hard graft.

For example, if you plant a stone from a Stella cherry, the seedling will not grow into another Stella. You likely will not get stellar results and won’t be raising a pint of Stella to celebrate. Instead, it will be a new, genetically unique cherry tree. Because Stella is self-fertile, the pollen parent might also be Stella, but the result is still a genetic reshuffle. The seedling could produce good fruit, but more often it’s unpredictable — sometimes smaller, more sour, or later to ripen. That’s why nurseries propagate Stella by grafting, not by seed.

That said, cherries grown from seed can still be valuable. They make attractive trees for wildlife and pollinators, provide excellent timber (cherry wood is prized in furniture so ideal for beginners looking to get wood and lose their furniture-making cherry in the workshop), and can even be used as rootstocks themselves once established[26]. Some gardeners enjoy raising cherry seedlings simply for the challenge or for the surprise of what fruit might appear. These gardeners have a lot of thyme on their hands.

If you want to try, cherry seeds need a cold stratification period — usually around 8–12 weeks in moist compost kept at fridge temperatures — to break dormancy before they will germinate[33]. Even then, patience is required: seedlings may take 7–10 years to produce fruit, and the results will be unpredictable. Best Eating Cherries for UK Gardens

Cherry picking the best is subjective because it may well be the rock star of fruit, but if it needs so much nurturing you have to read it a bedtime story, you won’t want it. Popular cherry trees have qualities such as flavour, reliability, self-fertility, resistance to splitting, and how well the tree copes with our climate.

Often Suggested “Best” Dessert Cherries

Lapins (‘Cherokee’) — Self-fertile, heavy crops of large, well-flavoured dark red fruit; reliable in UK gardens. RHS AGM: Yes [34][3][35].

Stella — The classic self-fertile garden cherry; large, rich fruit, regular heavy crops (can split in very wet spells). RHS AGM: Yes [50].

Sunburst — Self-fertile, large very dark red cherries with good flavour in mid-season. RHS AGM: No [36].

Sweetheart — Self-fertile, very late cropper with a long picking window of sweet dark-red fruit; precocious. RHS AGM: Yes [37].

Summer Sun — Productive mid/late-July cherry noted by UK sources for coping with cooler, dull summers; not self-fertile. RHS AGM: Yes [38].

Kordia — Large, firm “black” cherries, good flavour; some crack resistance; not self-fertile. RHS AGM: Yes [156].

Sylvia — Naturally compact/columnar habit (good for pots), large firm dark cherries; partially self-fertile (better with a partner). RHS AGM: No [157].

Regina — Late, firm dark cherries with good crack resistance; needs a pollinator. RHS AGM: No [158].

Penny — British-bred, very late season, large firm dark fruit; compact tree; not self-fertile. RHS AGM: Yes [159].

Merchant — Early, reliable heavy crops of well-flavoured dark fruit; not self-fertile. RHS AGM: Yes [160].

Celeste (‘Sumpaca’ PBR) — Early, self-fertile, naturally less vigorous (2–3 m), sweet dark-red fruit; ideal for small gardens/containers. RHS AGM: No [161].

Skeena — Modern self-fertile dark cherry producing very large, firm fruit; widely praised in comparisons. RHS AGM: No [162].

These varieties consistently feature in RHS lists, UK nursery catalogues, and expert recommendations.

How “Best” Is Decided

Expert reviews & awards – RHS Awards of Garden Merit, nursery trials, and decades of gardener feedback carry weight.

Sales & consumer demand – UK shoppers overwhelmingly prefer British-grown cherries; seven of the top 10 selling varieties are home-produced[39].

Flavour & storage – Some cherries taste phenomenal but bruise quickly; others like Lapins combine flavour with firmness, making them favourites for both gardens and supermarkets.

Ease of growing – For many gardeners, self-fertility is the clincher (for the cherry, not themselves)

Location and Climate Factors

Northern or cooler sites – Varieties like Summer Sun (bred in the UK) and sour Morello cope better with chillier weather[40].

Frost pockets or semi-shade – Morello cherries tolerate colder, less sunny sites than sweet cherries.

Wet summers – Splitting becomes a risk; Lapins and Sylvia cope better by either resisting cracks or hiding fruit beneath leaves[41].

Small gardens – Compact, self-fertile types (Stella, Lapins, Sylvia) on dwarfing rootstocks like Gisela 5 are best choices.

Weather Makes the Difference

Cherries are dramatically influenced by seasonal weather.

Warm, dry summers = plumper, sweeter, firmer cherries (2025 produced the UK’s largest cherry crop in years)[42].

Wet spells at ripening = higher risk of fruit splitting and softer cherries.

Milder springs = longer UK cherry season, sometimes nearly doubled compared with a decade ago[43].

Takeaway, by that we mean opinion and not Chinese.

The best UK eating cherries are not chosen on taste alone. They’re backed by RHS awards, expert reviews, consumer preference, and resilience to the UK’s unpredictable weather. Your own “best” will depend on garden size, location, and whether you want early or late fruit.

Dwarf / Small-Garden Options

Not everyone has the space for a cherry tree that can grow to 6 m high. Luckily, dwarfing rootstocks mean you can enjoy cherries even in a modest back garden or on a patio.

What Is a Dwarfing Rootstock?

In short, the roots of another tree. Usually from a Prunus avium, hybrids of Prunus avium, hybrids of Prunus cerasus + Prunus canescens and Prunus fruticosa (dwarf cherry) and Prunus cerasus. These give you rootstocks such as Mazzard, Colt, Gisela 5, Gisela 6, F12/1 and Krymsk.

By carefully selecting the rootstock, breeders can control the eventual size, vigour, and productivity of the tree[44].

This is how you can get one Stella tree to grow to 3m while another grows to 6m. Still the same tree, just grafted onto different rootstock.

How Is Dwarfing Achieved?

Dwarfing is the result of natural genetic traits in the rootstock. Some cherry rootstocks naturally produce smaller, less vigorous growth.

Grafting a piece of another tree (scion) onto these rootstocks restricts sap flow and growth hormones, which keeps the canopy compact without affecting fruit quality.

This allows nurseries to tailor cherries for orchards, gardens, or patios simply by changing the rootstock—not the fruiting variety itself[44][45].

Pros of Dwarfing Rootstocks

Manageable size – easier pruning, netting, and harvesting without ladders[46].

Earlier cropping – dwarf trees often fruit 1–2 years earlier than vigorous ones[44].

High yields per square metre – compact trees channel energy into fruit rather than endless wood growth.

Better suited to containers or small gardens.

Cons of Dwarfing Rootstocks

Shallower roots – less drought-resistant; need regular watering and mulching[45].

Shorter lifespan – may live 15–20 years, versus 30+ years for vigorous trees.

More prone to leaning – sometimes require staking for life.

Lower ultimate yield – while yields per area are high, one tree will give less overall than a large vigorous tree.

Common Cherry Rootstocks And Their Benefits

Gisela 5 – Semi-dwarf. Final height ~3 m. Precocious (fruits early), high-yielding, but needs good soil and support. Excellent for small gardens and containers[44].

Colt – Semi-vigorous. Final height ~4–5 m. Hardy, adaptable, tolerates poorer soils. A good all-rounder for UK gardens that still want “big tree presence” but not unmanageable growth[46].

Mazzard (Prunus avium seedling) – Vigorous. Final height ~6 m. Traditional orchard rootstock, long-lived, but far too big for small gardens[45].

Gisela 3 / Gisela 6 – Less common but offer variations in dwarfing strength; Gisela 3 very dwarfing (rare in the UK), Gisela 6 is slightly larger and more tolerant of stress[44].

Which Rootstock Should You Choose?

Tiny gardens / containers – Gisela 5 (precocious, compact, heavy cropping).

Medium suburban gardens – Colt (manageable with pruning, reliable, hardy).

Large plots or traditional orchards – Mazzard (long-lived, big, and impressive).

Takeaway

If you’re short on space, the rootstock is as important as the variety. A Lapins on Mazzard might need a cherry-picker; a Lapins on Gisela 5 can live happily in a pot. Dwarfing rootstocks don’t change the fruit—just the size, manageability, and how quickly you’ll enjoy your first harvest. For most UK gardens, Gisela 5 or Colt will strike the best balance between flavour, yield, and practicality.

Where to Plant Cherry Trees in the UK

Easy! On land that you own because the council don’t like random orchards on their motorway roundabouts.

A well-placed cherry tree will flower well in spring and provide plenty of fruit in summer; a poorly placed one will sulk, split, or just refuse to perform. If you get lots of flowers unexpectedly, someone might think you’ve taken up baking.

Do Cherry Trees Need Full Sun?

The sweet dessert cherries do — they thrive in full sun. Sunshine not only boosts flowering and fruit ripening but also reduces disease risk by keeping leaves drier [3], making it harder for fungal diseases like canker and blossom wilt to take hold. Shade-grown dessert cherries tend to be leggy, with fewer flowers and lower-quality fruit.

Sour cherries (like Morello, Prunus cerasus) are more tolerant of partial shade, making them a good option for north-facing walls or shadier plots [47]. You can talk to it in shades of grey, show it shady behaviour, shout that it is a pale shade of a dessert cherry, and throw it some shade — and it will still perform — but you can’t keep it in the dark.

Soil & Drainage Requirements

Free-draining soil is crucial. Cherries hate “wet feet” and are prone to root and bacterial problems in waterlogged ground [48].

They prefer deep, fertile, moist-but-well-drained soil [3] with a pH of slightly acidic — around 6.5–6.7, according to RHS advice [3].

How Far from the House?

This depends on the rootstock used. Simplified, the taller the tree, the further the roots grow. The further the root from the tree, the smaller the roots will be and less of a problem. Cherry trees are shallow roots so old clay drains, paving slabs etc might be affected. It is worth while knowing how far the roots grow because they might grow into something like old builders rubble buried in the back garden and alkaline cement bags have caused problems historically.

How Far Apart to Plant?

Why is spacing important when planting cherry trees? [51]

Proper spacing improves airflow (reducing fungal problems), light exposure (better blossom and ripening), reduces root competition for water and nutrients, and leaves access for pruning, netting and harvesting.

Does spacing depend on the rootstock?

Yes. Rootstock dictates eventual size and spread (e.g. Gisela 5 is semi-dwarf; Colt is semi-vigorous), so spacing scales with vigour. [3]

How far apart should dwarf or semi-dwarf cherries be planted?

On Gisela 5, plant about 3.0–3.5 m apart (10–11.5 ft). This balances airflow and access while keeping trees compact for smaller gardens. [53]

How far apart should semi-vigorous cherries be planted?

On Colt, allow roughly 3.6–4.5 m (12–15 ft) between trees. Colt is common in UK gardens and produces medium-sized trees that still need space for pruning and netting. [49]

How far apart should vigorous cherries be planted?

Mazzard / F12/1: use 6–8 m (20–26 ft) for standard orchard-style spacing; 8–10 m if you want wide alleys and maximum airflow. [49]

Can I plant cherry trees closer if I prune them?

Yes, within reason. Training (e.g. fan-training) and consistent summer pruning let you keep trees narrower. As a rule of thumb, fans are often set around ~2.5 m apart; note that a mature fan on Gisela 5 can reach ~3.5 m wide if you let it. [54]

How close do cherry trees need to be for pollination?

For cross-pollination, a practical rule is to keep compatible trees within about 18 m (55 ft) so pollinators can move easily between them. (Self-fertile cultivars still benefit from a partner nearby.) [55]

Can I plant cherries in a row or hedge style?

Yes — if you train them (fans/espaliers). Typical advice is ~2.5 m between fan/espalier trees along a wall or fence, provided you maintain their width with pruning. [54]

What spacing is best against a wall or fence?

Plant 20–30 cm out from the base of the wall/fence to avoid the driest soil, then allow ~2–3.5 m width per trained tree (depending on rootstock and how strictly you prune). [57]

What happens if I plant cherry trees too close together?

You’ll get shading (poorer crops), reduced airflow (more disease), root competition (slower growth/less resilience), and poor access for pruning, netting and picking. [51]

When & How to Plant

Best Time of Year (Bare-Root vs Container)

Bare-root cherries should only be planted during dormancy, November–March in the UK, provided soil is not frozen or waterlogged.

What is dormancy? Dormancy is the tree’s “resting phase” — it has no leaves, no active growth, and very low metabolic activity. In this state, roots can be disturbed and replanted with minimal stress [58].

Why bare-root cannot be planted outside dormancy: Once buds swell or leaves emerge, sap is flowing and roots need a constant supply of water. A bare-root tree at this stage will dry out rapidly and often die if not planted.

How to recognise dormancy ending: Signs include swelling buds, visible green tips, or new leaf growth. A quick check is the “scratch test”: gently scratch a bud — if green tissue is showing, the tree is waking up and should be planted immediately.

If you cannot plant right away: Preserve dormancy by “heeling in” (temporarily covering roots with moist soil or compost outdoors) or keeping roots wrapped in damp sacking/coir in a cool, shaded, frost-free place. The aim is to keep roots moist, cool, and dark until planting [59].

Container-grown cherries can technically be planted year-round, because roots stay in their soil/rootball. However, the best establishment occurs in autumn (Sep–Nov), when soil is still warm and moisture is rising, and spring (Mar–Apr), when roots naturally resume growth. Winter planting is possible, but root growth is minimal until soils warm; summer planting works but requires vigilant watering and mulching to avoid stress [58][60].

Planting Bare-Root Cherry Trees In The UK

When to buy & plant

Buy dormant trees only. Purchase and plant November to March while fully dormant (no leaves). If bare root plants are available in April, we either had a cold spell, the nursery uses cold storage or you are taking a risk buying them. If there are leaves or buds starting to burst, don’t buy. You can plant immediately but it is a risk.If you can’t plant straight away in the dormant season.

If not planting straight away then you canh eel-in (best for weeks): In a sheltered, well-drained spot, dig a trench; splay roots and cover with moist soil/compost; firm lightly. Good for 2–6 weeks (weather-dependent).

Short hold (days): Keep roots wrapped in damp (not wet) material (coir/compost/sphagnum), bagged; store cool, dark, frost-free.

If buds begin breaking in storage, plant at once (or pot up) and keep cool and evenly moist.

Site check & drainage (do this first)

Percolation test

Dig a hole 30–40 cm deep, fill with water and let it drain. Refill once more.

If the water is still sitting after 12 hours then drainage is poor so plant on a raised mound or improve drainage before doing anything else.

If you have a clay layer, sometimes you can dig through it to get better draining soils. Soil pH

Cherries prefer pH 6.5–7.5.

If too acidic: add lime.

If strongly alkaline: incorporate organic matter to improve nutrient uptake.

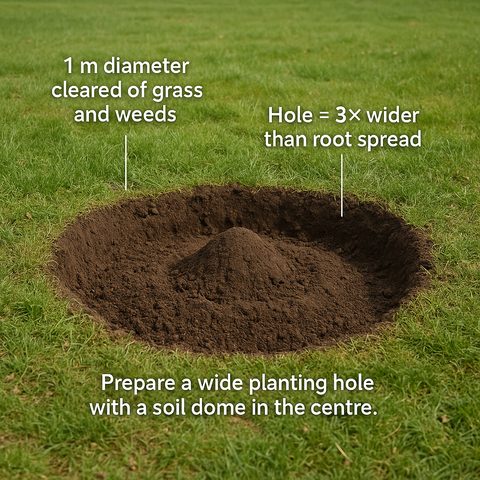

Weed-free circle

Once drainage and soil are confirmed suitable, mark and clear a 1 m diameter circle of grass and weeds to reduce root competition.

Dig the hole & set the height

Size

Dig the hole about three times wider than the root spread, and only as deep as needed so the base of the trunk (where it flares into the top roots) will sit at soil level. If in doubt, dig a touch deeper — you can adjust the final height with the soil dome. If you put any soil back in to raise the height, be sure to firm it down to prevent the tree from sinking.

Soil dome

Build a firm mound of soil in the middle of the hole. It needs to be firm to stop the tree sinking and lets the roots slope gently outwards and downwards. Build the dome so that the roots will be around 45 degrees to the horizon i.e. pointing them towards the bottom of the hole.

Spread roots

Lay the roots evenly over the dome, spreading them out like spokes on a wheel. Make sure the finished soil line will match the original mark on the trunk created by the previous soil level.

Why it matters

Spreading the roots out stops them curling round on themselves, gives the tree a firm hold against wind from all sides, and helps it grow into the soil evenly all around.

Roughing the sides

If the sides are smooth and shiny from digging, roughen them so roots can grow through. This is common with clay soils.

Backfill (what to use—and avoid)

Use native topsoil, crumbled fine; backfill and firm gently in stages to remove air gaps—don’t stamp.

Do not add fertiliser or manure in the hole (risk of root burn, later sinkage burying the flare/graft, and “flowerpot effect” trapping roots in the pit).

Put organics on top as mulch, not in the backfill.

Why friable (crumbly) backfill matters

Most uptake happens via microscopic feeding root hairs. Friable, crumbly soil makes intimate contact with those hairs. Great lumps of clay need to be broken up.

Water, stake, mulch

Water in thoroughly to settle soil and eliminate voids.

Stake (only if needed see our article ). In short, if you are in a walled, fenced or surrounded garden, you likely won’t need to stake. If in doubt, use a short, single stake on the upwind side; one flexible tie 30–45 cm above soil so the trunk can flex slightly. Remove after 2-3 seasons.

Mulch: 5–8 cm organic mulch across the 1 m circle, leaving a 5–8 cm mulch-free collar around the stem.

Wet or heavy soils (workaround)

See Planting On A Raised Mound.

Optional: Mycorrhizae

Mycorrhizal inoculants (e.g., Rootgrow®) can aid early establishment on poor, sandy or disturbed soils. Benefits are site-dependent and often modest on good loams with proper mulching and watering. They don’t replace correct depth, drainage, and aftercare.

Protection (as needed)

Guards/fencing where rabbits/deer are present.

Keep the mulch-free collar visible to avoid strimmer damage; consider a rigid spiral or mesh guard in high-risk areas.

Remove/tweak labels/ties that could girdle the stem as it thickens.

Aftercare (first 1–2 seasons)

Watering: Check soil moisture before watering. Push a finger or trowel 10–15 cm into the soil near the root zone — if it feels dry and crumbly, water; if still moist, wait. A simple moisture meter can help, aiming for “moist” rather than “wet.” Watch the tree too: wilting, dull leaf colour, or early yellowing leaves are signs of drought stress. In dry spells, give a deep soak so water penetrates to spade depth, usually every 7–10 days (more often on sandy soils).

Weed & mulch: Keep a 1 m circle around the trunk weed-free. Top up mulch each year, but keep it clear of the stem to prevent rot and pests.

Staking: Inspect ties monthly and loosen as the trunk thickens. Remove the stake once the tree passes the “wiggle test” (the trunk flexes but the rootplate stays firm), usually after 18–24 months.

Feeding: Monitor growth in spring. If shoots are weak or leaves pale, apply a light, balanced surface feed or mulch with compost. Avoid heavy nitrogen fertilisers, which produce soft growth prone to disease.

Pruning cherries: Prune only in late spring or summer (unless pruning out damage), and choose a dry spell to lower canker risk. Focus on formative pruning — shaping the young tree into an open, balanced framework.

Quick pitfalls checklist

Flare/graft buried will lead to rot, poor vigour

The root flare (where the trunk widens into roots) must sit at or just above soil level. If it’s buried, bark tissues stay damp and rot, and gas exchange is restricted. If the graft union is buried, the scion may root from above it, defeating the purpose of the rootstock.

Glazed pit sides will lead to roots stall

On clay soils, digging can smear the sides of the planting hole into a smooth “glazed” surface. Roots hit this barrier and spiral rather than penetrating, leaving a tree that is slow to establish or unstable. Roughening the sides with a fork breaks this up.

Fertiliser/manure in the hole will lead to burn / sinkage / “flowerpot effect”

Fresh manure or concentrated fertiliser can scorch fine root hairs. Organic matter decomposes and shrinks, causing the tree to sink and bury the flare/graft. A rich pocket in the pit also creates a “flowerpot effect,” where roots circle inside instead of spreading into the surrounding soil.

Roots bunched to one side will lead to poor anchorage / lean

If roots are clumped together or not spread radially, the tree anchors unevenly. Wind pressure then pulls harder on one side, risking lean or windthrow. Even spreading gives balanced support and better access to soil resources.

Mulch on trunk will lead to rot / rodents

Mulch piled against bark traps moisture against the stem, softening tissues and inviting fungal decay. It also creates cover for voles or mice, which may gnaw the bark at ground level. Always leave a mulch-free collar (? 5–8 cm).

Roots ever allowed to dry ? high failure risk

Fine root hairs die quickly if exposed to air or sun. Even a few minutes of drying can cause permanent loss of root function. Keep roots covered and moist from lifting through to planting.

Planting Container-Grown Cherry Trees

When to plant container trees

Planting Container-Grown Cherry Trees

When to plant container trees

Container cherries can be planted year-round if soil isn’t frozen or waterlogged; autumn to early spring gives the best establishment in the UK climate ([3], [58], [59]). Summer planting is possible but increases water-stress risk, so plan for diligent irrigation.

Choose the right spot

Full sun & shelter: cherries crop best with good light and protection from strong winds; avoid frost pockets ([3], [51], [104]).

Free-draining soil: cherries resent “wet feet”; on heavier ground improve drainage or plant slightly raised ([3], [59], [146]).

Against walls/fences (fans): set trees 20–30 cm out from the base to avoid the dry rain-shadow; install wires first ([10], [57], [82]).

Space & access: allow light and airflow for easier pest/disease management and picking ([51]).

Make the site favourable

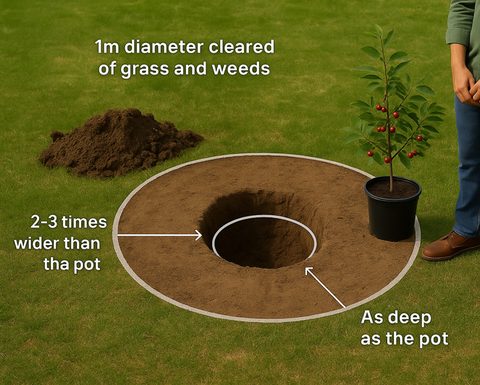

Weed-free circle: clear grass/weeds over ~1 m diameter and keep it that way with mulch ([73], [99]).

Heavy/wet soils: raise the planting area ~10–15 cm across a 1–1.2 m bed (higher if you have standing water) to keep roots above poorly draining soil ([59], [146]).

Prepare the tree

Water the pot 45–60 minutes before planting so the rootball is evenly moist ([58]).

Remove & loosen roots: slide the tree out; tease congested/circling roots so new roots grow outward—avoid leaving a smooth “pot-shape” mass ([58], [60]).

Dig the hole (the right way)

Size: make it 2–3× wider than the pot and no deeper than the rootball ([58]).

Base & sides: keep undisturbed soil at the base so the tree won’t sink; roughen sides so roots can penetrate (avoid glazing) ([58]). If you dug too deep, backfill and firm the base before positioning the rootball.

Backfill soil: keep topsoil separate from subsoil. If the soil is very poor, you may mix in some compost with the backfill sparingly—see the caveat below ([58], [60]).

Planting height: set the tree so the root flare is at or just above finished soil level, and keep the graft union above soil/mulch (do not bury the graft) ([58], [59]).

Why not manure or fertiliser in the hole?

Root burn: concentrated nutrients or fresh organic matter can scorch fine roots; even well-rotted manure can release salts/ammonia harmful at close quarters ([58], [59]).

Sinkage: organic matter shrinks as it decomposes, causing the tree to settle too low and potentially bury the graft/flare ([59], [146]).

“Flowerpot” effect: a pit filled with looser/richer soil can trap roots, discouraging them from entering the surrounding ground ([60]).

Best practice:

Backfill mainly with the native topsoil.

Put organic matter on top as a surface mulch (5–8 cm), kept clear of the trunk, so nutrients leach down gradually ([73], [95], [99]).

On poor soils, improve the wider bed or use a raised mound, not just the pit ([146]).

Signs your soil needs improving before planting cherries

Drainage problems – Percolation test: dig 30–40 cm deep, fill with water, let it drain, then refill. If water remains after 24 hours, drainage is poor ([3], [59], [146]). Other clues: mossy lawn, standing water after rain, sticky soil in winter.

Soil texture extremes – Heavy clay (sticky wet/hard dry) or very sandy (drains too fast) both benefit from organic matter added across the whole bed ([59], [146]).

Compaction – If a spade is hard to push in or soil lifts in shiny slabs, break up the structure and incorporate organic matter broadly ([146]).

pH imbalance – Cherries prefer pH ~6.5–7.5 ([14]). Test with a simple kit; lime acidic soils; add organic matter to help buffer high pH.

Low organic matter – Pale, lifeless soil with few worms: add compost or well-rotted manure as mulch annually ([73], [99]).

Quick rule of thumb

Good soil: moist but free-draining; crumbly; spade enters without force; holds moisture without puddling; pH neutral to slightly alkaline.

Needs work: sticky/soggy, very sandy/bone-dry, compacted, very acidic, or low in organic life.

Stake (if needed)

See our staking guide: or ([58], [70]).

Context: We planted 40 various bare-root trees/rootstocks in a garden with low boundary hedges with housing on all sides and none required staking; conditions vary, so assess your site. The previous link discusses wind rock to help you assess.

If staking: drive a short stake on the upwind side before backfilling; tie with rubber ties (not too tight). Remove once the tree stands firm (often after the first season or two) ([58], [70]). Do not use string or wire, which can cut into bark.

Firming: backfill and firm gently in lifts to remove voids—don’t stamp hard ([58], [60]).

Water & mulch (finish)

Water in thoroughly after planting to settle soil and eliminate air pockets ([58], [60]).

Mulch: apply 5–8 cm of organic mulch across the ~1 m circle, keeping a 5–8 cm mulch-free collar around the stem to avoid rot and pests ([73], [95], [96], [97], [99]).

Wet or heavy soils (workaround)

See Planting On A Raised Mound. .

Aftercare (first 1–2 seasons)

Watering: Check soil moisture before watering. Push a finger or trowel 10–15 cm into the soil near the root zone — if it feels dry and crumbly, water; if still moist, wait. A simple moisture meter can help, aiming for “moist” rather than “wet.” Watch the tree too: wilting, dull leaf colour, or early yellowing leaves are signs of drought stress. In dry spells, give a deep soak so water penetrates to spade depth, usually every 7–10 days (more often on sandy soils).

Weed & mulch: Keep a 1 m circle around the trunk weed-free. Top up mulch each year, but keep it clear of the stem to prevent rot and pests.

Staking: Inspect ties monthly and loosen as the trunk thickens. Remove the stake once the tree passes the “wiggle test” (the trunk flexes but the rootplate stays firm), usually after 18–24 months.

Feeding: Monitor growth in spring. If shoots are weak or leaves pale, apply a light, balanced surface feed or mulch with compost. Avoid heavy nitrogen fertilisers, which produce soft growth prone to disease.

Pruning cherries: Prune only in late spring or summer (unless pruning out damage), and choose a dry spell to lower canker risk. Focus on formative pruning — shaping the young tree into an open, balanced framework.

Rootgrow / Mycorrhizal inoculants

What it is: Mycorrhizal fungi (e.g., Rootgrow®) colonise roots and may aid water/nutrient uptake.

Pros: may improve establishment on poor/sandy/disturbed soils; easy to apply.

Caveats: effects are site-dependent; benefits are often modest in fertile loams with good mulching and watering (see [59], [73]).

Bottom line: optional—more useful on poor/disturbed sites; not a substitute for correct planting, drainage, mulching and watering.

Protection (as needed)

Use guards or fencing where rabbits/deer are present; keep the mulch-free collar visible to reduce strimmer damage.

Quick pitfalls checklist

Hole too deep ? flare/graft buried ([58], [59]).

Glazed pit sides ? roots stall ([58]).

Fertiliser/manure in the hole ? sinkage/root burn ([58], [60]).

No stake in windy sites ? rootball rocks, breaks fine roots ([58], [70]).

Mulch against trunk ? rot/rodents ([73], [95], [96], [97], [99]).

Grass re-encroaches into the 1 m circle ? water/nutrient competition ([73], [99]).

Planting On A Raised Mound.

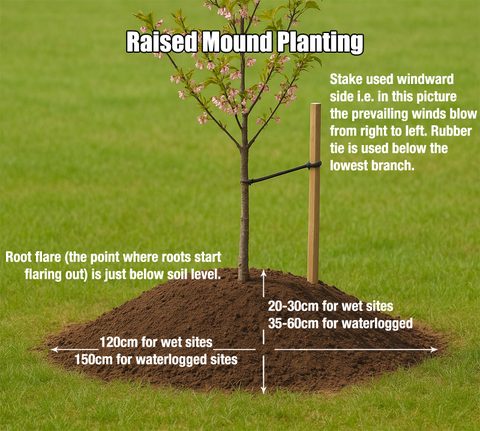

Why raised mounds?

Cherry trees — like most fruit trees — will not tolerate “wet feet.” In poorly drained or heavy clay soils, water lingers around the roots, starving them of oxygen and increasing the risk of root rot. Planting on a raised mound lifts the root system above the saturated zone, giving better aeration, faster warming in spring, and healthier root growth [58][59].

When to use one:

Heavy or compacted clay that stays wet 12 hours after rain has stopped.

Sites with a high water table.

Anywhere waterlogging has killed or stunted trees before [58][59].

How high and wide should it be?

Normal heavy soils: 20–30 cm high, at least 1–1.2 m across.

Very wet soils: 45–60 cm high, at least 1.5 m across (go wider if space allows).

Always keep the mound broad and domed — shallow slopes stop the soil washing away [170][171].

How to make it step by step:

Mark out the pad — clear a circle at least 1–1.2 m in diameter (larger for wetter soils).

Build the mound — heap good topsoil into the centre, forming a dome. Avoid piling raw subsoil or debris into the mound; use your best available soil.

Firm the mound — tread lightly to settle the soil so it won’t collapse under the tree’s weight.

Check the height — the crown of the mound should be 20–30 cm (or 45–60 cm for poor sites) above the surrounding ground.

Plant the tree — spread the bare roots radially over the dome. The root flare (where trunk thickens at the base) must end up level with, or just above, the finished surface.

Backfill and mulch — cover roots with the mound soil, firm in, water well, and mulch the surface (but keep mulch clear of the trunk) [95][96][97].

Key points:

Don’t add fertiliser or manure into the mound when planting — it can scorch new roots [103].

Shape the mound with gentle sides so it integrates with the surrounding ground.

Mulching is essential: raised soil dries out faster in summer [95][96][97].

Stakes are still recommended on raised mounds, since the soil is looser and trees may rock until roots anchor [70].

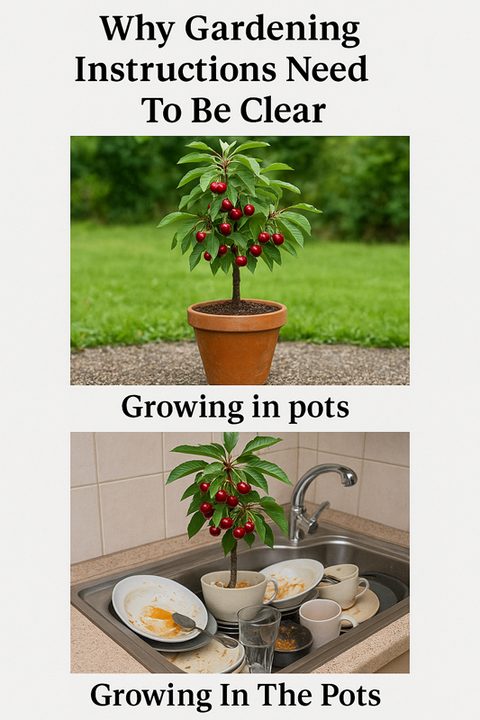

Growing in Pots/Containers

Can you grow cherry trees in pots in the UK?

Yes — cherry trees can be grown successfully in pots in the UK, provided you choose a suitable variety, give them enough space (in terms of pot size), and care properly for their needs (watering, feeding, winter protection). Container growing is more demanding than planting in the ground (pots dry out faster, roots are more exposed), but many gardeners do this, especially where garden space is limited or for patio/balcony planting [61].

What’s the best cherry tree for pots in the UK?

Some varieties are especially well suited to containers, particularly those that are self-fertile, dwarf (e.g. Gisela 5, mature height ~2.5–3 m) or semi-dwarf (e.g. Colt, mature height ~3.5–4 m) rootstocks, or otherwise compact. A few examples:

Morello (Prunus cerasus ‘Morello’) — a sour cherry that is self-fertile, can be grown as a dwarf or semi-dwarf, and works well in pots [63].

Stella — often cited among self-fertile cherries suitable for container growth [61].

Lapins — another good choice, especially for larger pots or where you want dessert cherries with less worry over pollination [61].

Also, look out for varieties with the RHS Award of Garden Merit, or those labelled “patio” fruit trees, dwarf, semi-dwarf, etc. [3].

Do potted cherry trees still need another tree for pollination?

It depends on the variety:

Self-fertile cherries do not need a second tree. These varieties have flowers that can pollinate themselves (or with some insect aid), so you can get fruit from a single tree. Morello, Stella, and others are self-fertile [61].

Self-sterile varieties do require a pollination partner — another cherry tree that flowers at roughly the same time — to set good crops. Even self-fertile trees tend to give better yields if there is a compatible partner nearby [3][62].

So if you have limited space (one pot only), picking a self-fertile compact variety is safer.

How big will a cherry tree in a pot grow?

What size a potted cherry reaches depends on:

The rootstock (dwarf vs semi-dwarf vs full). Dwarf rootstocks like Gisela 5 usually keep a tree to a mature height of ~2.5–3 m, while semi-dwarf rootstocks like Colt reach a mature height of ~3.5–4 m [3].

The size of the container: larger, deeper pots allow more root growth, which usually means more top growth. If the pot is too small, growth (and fruiting) may be limited [61].

Pruning and management also matter (cutting back, controlling shape).

As a rough guide, a cherry tree on a small to moderate dwarf rootstock in a large enough pot might stay at 1.5–2.5 m (5–8 ft) under good care, though fully grown cherries on more vigorous rootstocks will want ground space.

Pot & Soil Choice

What size pot do I need for a cherry tree?

Go as large as you can manage: RHS advises 45–50 cm (18–20 in) diameter for most fruit in containers, which also works for cherries [64][3]. For long-term container growing (several years), The Orchard Project recommends at least 60 cm deep and 60 cm wide, with ~1 m × 1 m ideal for bigger root systems [65]. Orange Pippin adds that containers under 50 cm are unlikely to be big enough, and that 60 cm+ is preferable for most new fruit trees [66].

What’s the minimum depth and width for the container?

Practical minimum: about 45–50 cm wide and deep to avoid the tree becoming pot-bound too quickly and to keep moisture more stable [64][3]. If you want the tree to live in a pot for years, aim for 60 cm+ each way [65][66].

Can I start small and pot up later?

Yes, but plan for regular repotting and closer watering. You can start smaller, then step up sizes; however, both RHS and specialist guides emphasise that larger volumes are more forgiving (moisture/nutrients) and that using a large final container from the start is often better for fruit trees than frequent potting-up, provided drainage is good [64][66]. Avoid “over-potting” with pure, fine compost that stays wet — use a soil-based medium and ensure free drainage [66].

What type of compost or potting mix should I use?

Use a loam-based, peat-free medium: John Innes No. 3 or a multi-purpose compost mixed with horticultural grit (RHS) [64][3]. This gives structure, aeration and water-holding without waterlogging. Orange Pippin also recommends a soil-based mix with ~20–30% grit for drainage [66].

Should I add grit or perlite for drainage?

Yes. RHS specifically advises mixing one-third by volume grit or perlite into the compost for container fruit, plus crocks over the drainage holes to keep them clear [64]. Orange Pippin likewise recommends ~20–30% grit and large pebbles/broken pot pieces at the base to maintain clear outflow [66].

Should I line or insulate the pot against frost or heat?

In winter, container roots are exposed on all sides and can freeze. RHS advises grouping containers in a sheltered spot and wrapping pots with bubble polythene or straw to prevent root freeze [67]. It also helps to raise pots on feet/bricks to improve drainage and reduce freeze damage to pots [68].

How do you plant a cherry tree in a pot step by step?

Choose a pot with good drainage holes, large enough for the root ball with room to grow — ideally at least twice the size of the root ball in both width and depth. Fill the bottom with a well-draining compost mix [3][71].

If the tree is containerised, gently tease out or loosen the roots, especially any circling or compacted ones. If it’s root-bound, prune back larger roots carefully [69][71].

Position the tree in the centre of the pot so that the graft union (if present) is at or just above soil level, not buried [3][69].

Backfill with a soil-based compost (loam-based or John Innes No. 3) or multi-purpose mix with some grit to improve drainage, tamp down lightly to remove air pockets [3][71].

Water well after planting to settle the compost around roots, ensuring moisture reaches throughout the root ball [61][71].

Mulch the top (keeping mulch slightly away from the trunk) to conserve moisture and reduce weeds [3][61].

Should I stake a potted cherry tree?

Yes, especially in the first year or if the tree is tall or in a windy location. Use a stake to support the trunk so it doesn’t flick in strong winds (which can damage the young root system) [70]. For container trees, single stakes are often enough, but ensure ties are loose enough to allow some movement, which strengthens the tree over time [70].

Do I need to prune roots when planting into a container?

You don’t always have to prune roots, but if the root ball is tightly bound (roots circling or very compact), it is beneficial to tease them out or trim some of the roots. This encourages roots to spread into the surrounding soil instead of staying in loops, helping with stability and water/nutrient uptake [69][71].

How do I avoid waterlogging in pots?

Use soil-based compost with good drainage (loam, grit, perlite) so water passes through rather than staying saturated [3][71].

Make sure drainage holes are clear and not blocked; raising the pot slightly helps water escape [3][71].

Don’t let pots sit in trays with standing water, especially in winter [61].

Should I use pot feet or raise the container off the ground?

Yes — raising the pot helps in several ways: improves drainage, prevents water logging under the pot, reduces frost damage from ground cold, and keeps the pot more stable. RHS and other guides recommend raising containers on pot feet or bricks [3][71].

Care & Maintenance Of Potted Cherries

How often should you water a cherry tree in a container?

Container trees dry out much faster than those in the ground. Keep compost evenly moist throughout the growing season and check more often in wind or sun; water deeply so moisture reaches the whole root ball [72]. Expect regular watering in warm spells (potentially several times per week for smaller pots) and little to none in winter dormancy (don’t let it sit waterlogged) [65][66].

(explainer: “waterlogged” = soil so saturated that air is excluded from the roots, leading to rot).

How do you feed or fertilise potted cherries?

Apply a controlled-release fertiliser in spring and/or a high-potassium liquid feed at intervals during the growing season to support blossom and fruiting (e.g., tomato feed, seaweed extract, comfrey tea) [72][65]. You can also top-dress in spring: scrape off about 5 cm of the surface compost and replace with fresh compost mixed with fertiliser [72].

(explainer: “high-potassium” = fertiliser high in the nutrient potassium, essential for flowers and fruit).

Do I need to repot, and how often?

Repotting is needed when roots circle tightly or growth slows. The Orchard Project recommends refreshing the compost and trimming roots every other year once the tree is established [65]. Orange Pippin advises replenishing soil and pruning back roots by ~25% every 3–5 years for long-term potted trees [66].

How do I root-prune a cherry tree in a pot?

At repotting, gently tease out circling roots and cut back thick loops. For mature trees, prune the outer root mass (around a quarter of the roots), then refill with fresh compost [65][66].

(explainer: “root pruning” = cutting back some roots to prevent the tree becoming pot-bound and to encourage new feeder roots).

What mulch works best in pots?

Mulch helps retain moisture, buffer soil temperature, and reduce weeds. Good choices include woodchip, leaf mould, or well-rotted compost [65]. RHS recommends applying organic mulch in spring or late winter, keeping it a few cm clear of the trunk [73].

Do I need to protect roots in winter from freezing?

Yes. Roots in pots are more vulnerable to frost. Group containers in a sheltered spot, wrap pots in bubble wrap or hessian, and raise them on feet or bricks to aid drainage. Avoid leaving pots standing in water [72][66].

How do I stop the soil drying out in summer?

Use larger pots — more compost holds moisture longer.

Apply mulch on the surface and shade pot sides if exposed to strong sun [65].

Water deeply and consistently; don’t rely on light rainfall [72][66].

Choose a loam-based compost mixed with grit for both water retention and drainage [72].

Fruiting & Pollination

Will container-grown cherries fruit as well as those in the ground?

They can crop well, but yields are usually smaller than in-ground trees. Restricted root space limits water and nutrient uptake, and drought stress can cause fruit to drop early. RHS stresses that container fruit trees need steady watering and feeding to sustain crops [64][3].

How soon will a potted cherry tree bear fruit?

Most cherries start producing fruit in about the fourth year after planting, though some dwarfing combinations may fruit slightly earlier with good care [74]. Growth in pots can be slower than in the ground, so patience is needed [3].

Do potted cherries still need pollination partners?

Yes — unless the variety is self-fertile. RHS lists self-fertile cherries such as ‘Stella’, ‘Lapins’, ‘Sunburst’, and the acid cherry ‘Morello’ [3]. These will fruit alone, but even self-fertile trees crop more heavily if another cherry flowers nearby.

(explainer: “self-fertile” = tree can pollinate itself; “self-sterile” = needs pollen from another compatible cherry).

Will the crop size be smaller in a pot?

Yes. Container cherries give lighter harvests than ground-planted trees because of limited root space and higher stress risk. With attentive watering, feeding, and pruning, you can still achieve worthwhile crops [64][3].

Problems & Risks

What pests and diseases affect cherries in pots?

Container cherries suffer from the same main problems as ground-grown trees:

Cherry blackfly (Myzus cerasi): sap-sucking insects that cause curled, sticky leaves at shoot tips. RHS notes they are unsightly but rarely reduce long-term tree health [78].

Brown rot: fungal disease that causes fruit to rot on the tree and can also affect blossoms [76].

Blossom wilt: blossoms and young shoots shrivel and die back in spring; can reduce cropping [77].

Bacterial canker: causes dieback, sunken patches on bark, and “shothole” leaves (small holes where spots fall out) [75].

(explainer: “shothole” = a pattern of small round holes in leaves after infected tissue drops out).

Does growing in containers increase the risk of root rot?

Yes. Containers make it easier to overwater or leave pots standing in water over winter, both of which suffocate roots and encourage fungal diseases like Phytophthora root rot. To reduce risk:

Use free-draining, loam-based compost.

Ensure drainage holes are clear.

Raise pots on feet or bricks.

Avoid saucers or trays that hold standing water [79][72].

(explainer: “root rot” = roots turning brown/black and mushy, unable to take up water or nutrients).

Can containers stunt the tree or reduce fruiting?

Yes — but this is partly intentional. Containers restrict root growth, keeping trees smaller and easier to manage. However, restricted roots mean trees have lower cropping potential compared to the same variety planted in the ground. RHS notes container cherries need disciplined feeding and watering to avoid poor growth and yield [64].

How do I tell if the pot is too small?

Warning signs include:

Compost drying out very quickly after watering.

Roots emerging from drainage holes.

Growth slowing or leaves yellowing despite regular feeding.

The root ball forming a dense, circling mat when lifted from the pot.

At this stage, either repot into a larger container or carry out root pruning with fresh compost [65][66].

Can a container tree blow over in the wind?

Yes — tall, narrow containers are prone to toppling. RHS recommends choosing wide, heavy pots (e.g. terracotta or stone), siting in a sheltered location, and raising on feet for stability [80][72]. Young trees in containers may also benefit from a stake until roots anchor well.

(explainer: “stake” = a support post tied loosely to the trunk to stop the tree rocking in wind).

Alternatives & Special Cases

Can cherries be grown in half-barrels or raised planters?

Yes. RHS confirms cherries grow well in large containers such as half-barrels, provided they are at least 45–50 cm deep and wide, filled with a soil-based compost like John Innes No. 3 [3]. Raised planters work the same way as oversized pots, but must have free drainage and enough depth for roots.

(explainer: “John Innes No. 3” = a loam-based potting compost with added nutrients, suited for long-term trees in pots).

Can I grow a cherry on a balcony?

Yes — as long as you can provide:

Full sun (6+ hours daily).

A large, stable container (?45–50 cm wide/deep).

Shelter from wind, since balconies can be exposed.

Careful watering (containers dry quickly in raised, windy sites).

Grouping pots together improves the microclimate (slightly warmer and less drying) [72][79].

(explainer: “microclimate” = the small-scale climate conditions around your balcony, affected by shelter, heat from walls, etc.).

Is espalier or fan training possible in pots?

Espalier cherries are not recommended — RHS states cherries are too vigorous for espaliers or cordons. However, fan training is well suited, especially against a warm wall, and works in a large container. Summer pruning after harvest keeps shape and allows easy netting [3].

(explainer: “fan training” = pruning and tying branches so they spread out flat like a fan against a wall or frame).

Can I keep a cherry permanently in a pot, or is it temporary?

Yes — with the right conditions. Choose a compact rootstock (e.g. Gisela 5), use a large container, and carry out repotting and root-pruning every few years. Orange Pippin notes container cherries can live long-term if the compost is refreshed and roots are periodically pruned back [66]. Without this, trees will decline after a few years [64].

Training Forms

What is a “form” of cherry tree?

A form is the deliberate shape/structure you train a fruit tree into (by pruning and tying) so it fits your space and crops well. Common forms for cherries are: bush (open-centre), half-standard/standard (longer clear stems), fan (flat against a wall/fence), and occasionally pyramid (kept with a central leader but not usually sold in the UK). Cherries are not suited to espaliers or cordons — those systems work far better for apples and pears [81][3].

(explainer: “clear stem” = the bare trunk before the canopy starts; “open-centre” = branches arranged so the middle of the tree is open for light and air).

If you’re an average gardener or in doubt, pick a bush or half-standard form — they’re the easiest to manage, prune, and net [81][3].

What is a bush cherry tree form?

RHS definition: Clear stem of about 75 cm (30 in) before the canopy starts [81].

Nursery variations: Many UK suppliers (e.g. Orange Pippin Trees) sell bush forms with shorter clear stems, around 30–50 cm [85].

Benefits: Manageable height for pruning and picking; good light and airflow; suitable for most gardens.

Who chooses it: Home gardeners and beginners who want a practical tree without ladders.

What is a half-standard cherry tree form?

RHS definition: Clear stem of about 1.35 m (4 ft 6 in) [81].

Nursery variations: Some UK nurseries (e.g. Frank P. Matthews) sell half-standards with ~0.8–1.0 m clear stems [84].

Benefits: Canopy begins higher up — easier to mow or plant underneath; looks more ornamental than a bush.

Who chooses it: Gardeners who want a tree that doubles as a lawn feature or shade provider.

What is a standard cherry tree form?

RHS definition: Clear stem of about 2 m (6 ft 6 in) [81].

Nursery variations: Standards are less often sold for cherries, but where offered, stem heights may vary slightly between suppliers.

Benefits: Large, traditional look; trunk shows off; canopy provides shade above head height.

Who chooses it: Larger gardens; those happy to manage pruning at ladder height.

What is a fan-trained cherry tree?

Description: Branches are spread flat like a fan on wires against a wall/fence. Cherries are best suited to fan training, not espaliers or cordons [81][3].

Size & setup: A wall or fence of ~2 m high is ideal; plant 15–22.5 cm from the wall. Typical mature sizes:

On Gisela 5 rootstock: ~1.8 m high × 3.6 m wide.

On Colt rootstock: ~2–2.4 m high × 5–5.5 m wide [82].

Benefits: Ideal for small gardens; a warm wall helps ripening; easy to net.

Who chooses it: Gardeners with limited space, or in cooler regions.

Care tip: Train and prune in spring/summer (in dry weather) to reduce risks of canker or silver leaf [83][86].

Can cherries be grown as espaliers?

Short answer: No. Espaliers (horizontal tiers) are too restrictive; cherries are too vigorous and crop poorly in this form [81][3].

Advice: Choose a fan or bush form instead.

Can cherries be grown as cordons?

Short answer: No. Cordons (single stems grown upright or at 45°) work for apples and pears, not cherries [81]. Cordons demand repeated pruning through the season; with cherries this increases the risk of canker/silver leaf, so stick to bush/half-standard or fan.

Advice: Use a fan where you need a space-saving cherry tree [3][82].

What is a pyramid cherry tree form?

Description: Central leader retained, with branches angled to form a pyramid. Branches start about 40–50 cm from ground and shorten up the tree to maintain the shape [7].

Benefits: Attractive and compact; suitable for structured orchards.

Who chooses it: Enthusiasts happy to prune regularly.

Note: RHS acknowledges cherries can be grown as bush, pyramid, or fan, but for most gardeners bush/fan are easiest [3].

What is an open-centre cherry tree form?

Description: The classic bush shape with 3–5 main branches trained outward, leaving the middle open for light and air [81].

Benefits: Excellent light penetration, airflow (reduces fungal disease), and easier access for pruning/picking.

Who chooses it: Most gardeners, especially those wanting a practical tree without complex training.

Care note: For cherries, prune in spring or summer (dry weather) to reduce bacterial canker or silver leaf risks [86][75].

Pruning

What is pruning?

Pruning is the selective cutting back or removal of parts of a tree — usually shoots, branches, or stems — to guide how it grows. It isn’t simply “tidying up.” With fruit trees, pruning is a tool for shaping the tree’s framework or branch structure, keeping it strong, and ensuring it stays productive over many years.

Done well, pruning is purposeful, not random: it builds a solid structure, directs energy into useful shoots, and removes growth that is weak, shaded, or diseased. Top tip to take away. If you prune a cherry tree too hard, it reacts by producing lots of vigorous upright water shoots instead of fruiting wood. This wastes energy, crowds the canopy, and delays cropping.

You can spot water shoots because they:

Grow straight up, often vertically from branches or the trunk.

Are much longer and faster-growing than nearby shoots.

Start out soft and green, then harden into woody upright stems.

Usually don’t carry flowers or fruit in their first years.

Why do we prune cherry trees?

Cherries have particular needs that make pruning especially important.

Light and fruiting – Cherries bear most of their crop on short spurs. These need good sunlight to stay productive and to form next year’s flower buds.

If left alone very long branches starting at the trunk can be prone to storm damage.

Disease control – A more open canopy improves airflow and reduces fungal and bacterial problems such as brown rot, silver leaf, and canker.

Renewing wood – Old or downward-hanging shoots often carry poor-quality fruit. Pruning encourages young, vigorous shoots that produce better crops.

Size and access – Regular pruning keeps cherries to a manageable shape and height, making picking and netting possible.

In short, pruning is what turns a cherry tree from a vigorous but unmanageable grower into a healthy, balanced tree that produces reliable crops.

What you must know first before hacking away

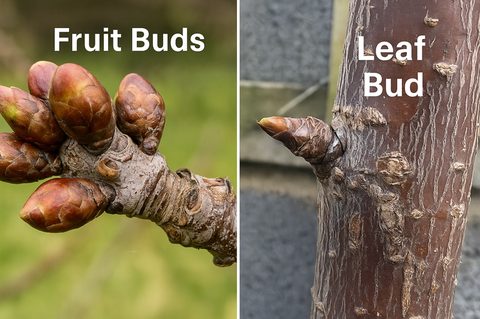

Recognising fruit and leaf buds

Cherry trees carry most of their crop on short, stubby shoots called fruiting spurs. These look very different from leaf buds:

Fruit buds are plump, rounded, and often clustered. These are on short stubby branches.

Leaf buds are flatter, narrower, more pointed and appear as single buds. They can plump up and look similar to fruit buds

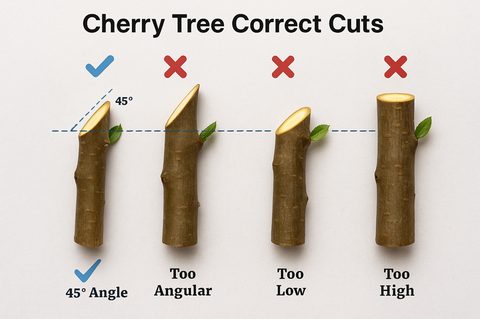

A spur can stay productive for several years, producing flowers and cherries each summer. When spur wood gets old, downward-hanging, or shaded, it’s replaced by younger shoots — but while it’s active, it’s the most valuable wood on the tree. Before making any cuts, learn to spot the difference. This ensures you don’t remove the very shoots that will carry next year’s crop. Tool sterilisation Sterilise all tools after cutting a diseased section. It is good practice to sterilise when moving to another tree too. Burn or dispose of diseased wood, you don’t want it in the garden e.g. compost. Where to cut Make each cut just above a bud that points outward, angling the cut slightly away from that bud so water runs off. If the nearest bud points into the centre, move to the next bud that points outward and cut there instead. This prevents branches growing into the middle.

Exception: when removing a whole branch, cut just outside the branch collar (use the three-cut method for big limbs); when cutting back to a side branch, cut to the side-branch union, not above a bud. Reducing Height Most cherries are carried lower down on spurs; the very top extension you shorten in late summer bears little or no fruit, so height cuts remove minimal cropping real estate.

Understanding “form” in cherry trees

A tree’s form is its overall shape or training system — the framework of branches that it will keep for its lifetime. Form isn’t just about looks; it affects how easy the tree is to manage and how well it will fit into the space available.

The four main forms used for cherries are:

• Bush – low framework with an open centre.

• Half-standard – taller clear trunk before the canopy starts.

• Fan – spread flat against a wall or fence.

• Pyramid – upright with a central leader and tapering sides (not usually sold in the UK)

The form is decided at the maiden stage (the tree’s first pruning at year 1). If you buy a maiden in the UK, they are usually bare root, very tall and require a prune to decide the form. After that, pruning mainly maintains the shape and renews productive wood rather than changing it completely.

Training forms for cherries

Bush / open-centre (goblet)

A bush cherry tree has a short trunk (about 40–60 cm) topped with 3–5 main branches that spread outward to form a rounded, goblet-shaped canopy. At maturity on a dwarfing rootstock (e.g. Gisela 5), the tree is typically 2–3 m tall and 2.5–3.5 m wide. On a semi-vigorous rootstock (e.g. Colt), it may reach 3.5–4.5 m tall and equally wide if not controlled. The centre of the tree is kept open to let in light and air.

Advantages of the bush form:

Compact and easy to fit into gardens.

Open centre improves light penetration and airflow, reducing disease.

Easy to prune, net, and harvest from ground level without ladders.

Starts cropping earlier on dwarfing rootstocks.

Suits close planting or small orchards.

Natural, informal look that blends well in gardens.

Half-standard

A half-standard cherry tree has a clear trunk of about 80–100 cm before the main branches start. Above this, the canopy is usually shaped like a bush, with 3–5 main branches forming an open-centre crown. On semi-vigorous rootstocks (e.g. Colt), a mature half-standard will usually reach 4–5 m tall and 3.5–4.5 m wide. On vigorous rootstocks (e.g. Mazzard), it can grow larger still unless pruned regularly.

Advantages of the half-standard form:

Canopy lifted higher off the ground, making it easier to mow or underplant beneath.

Less risk of damage from pets, strimmers, or lawnmowers compared with bush trees.

Provides more clearance for walking or working under the tree.

Attractive traditional orchard look.

Suited to larger gardens and open ground.

Fan-trained

A fan-trained cherry is grown flat against a wall, fence, or set of wires, with branches spread out and tied to create a fan shape. The clear trunk is usually only 30–60 cm high, after which 6–8 main arms are trained outward at angles. Mature fans typically cover an area about 2–3 m tall and 3–4 m wide, depending on the space and rootstock.

Advantages of the fan form:

Makes excellent use of vertical space — ideal for small gardens.

Walls and fences provide shelter and warmth, improving ripening.

Fruit is easier to net and protect from birds.

Very productive if pruned and trained regularly.

Allows vigorous rootstocks (Colt, Mazzard) to be controlled in a confined space.

Decorative and can double as a garden feature.

Why espaliers and cordons aren’t used for cherries

Cherries are not well suited to espalier (horizontal tiers) or cordon (single-stem) training. They are too vigorous, producing long, upright growth that does not settle into neat tiers or short-fruiting laterals like apples or pears. Attempts often lead to weak fruiting, poor structure, and increased disease problems. For cherries, bush, half-standard or fan are the reliable choices.

Pruning a 1 year old maiden cherry tree

A maiden cherry tree is a one-year-old young tree, usually a single whip (unbranched stem) or sometimes a lightly feathered stem with a few side shoots. Maidens are the starting point for creating any chosen tree form. The first pruning cut after planting is the most important, because it sets the framework the tree will keep for life. Do this with the maximum amount of time for dry weather to reduce disease risk and make it later winter to early spring.

For cherries in the UK, maidens are usually pruned into one of three forms: bush, half-standard, or fan.

Bush / open-centre (goblet) — maiden cut

After planting, cut the maiden back to about 30–40 cm above ground. Make the cut just above a bud that points outward so new growth heads away from the centre.

This shortens the main stem and prompts new shoots to break from buds just below the cut during summer. Don’t worry if the tree looks small — it’s meant to. Those shoots will form the main branch structure.

Aim to keep 3–5 well-spaced shoots the following year; remove or thin any extras to prevent crowding. If only two good shoots appear at the right height, let one strong side shoot develop from each the next summer to give you three or four evenly spaced main branches. It may sound like a low number, but these will be the branches that carry the tree going forward.

Half-standard — maiden cut

After planting, cut the maiden back to about 80–100 cm above ground level. This sets the height of the clear trunk before the canopy begins. New shoots will break from buds just below the cut during the summer, and these will form the start of the canopy.The following year, select 3–5 well-placed shoots to build the framework, as with a bush, but on a taller stem.

Fan-trained — maiden cut

After planting, cut the maiden back to about 30–40 cm above ground level, leaving three strong buds below the cut. In summer, the two opposite buds produce shoots that can be tied out at about 45° to start the fan arms, while the third can be kept as an upward extension. Remove or shorten any shoots pointing straight up or inwards to prevent congestion. A support system (wires or canes against a wall or fence) is essential from the start.

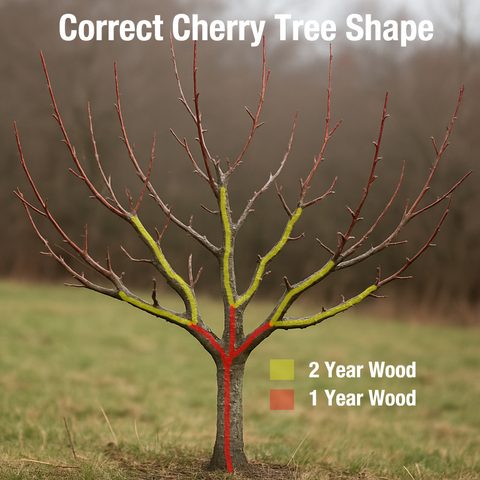

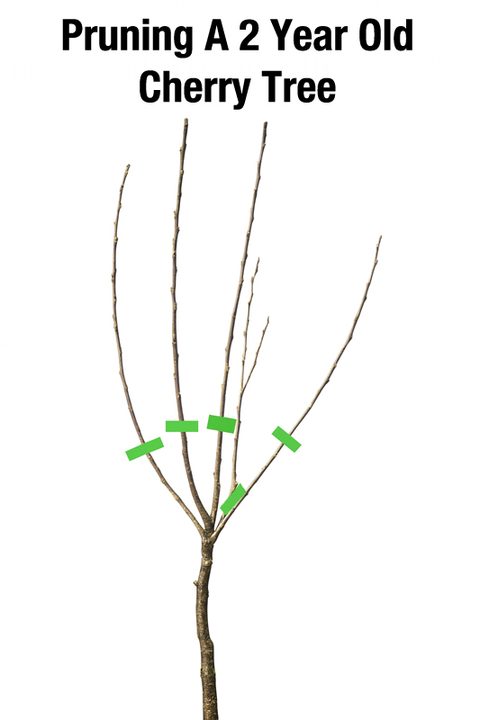

Formative pruning a 2–4 year old tree

The aim of formative pruning is to build a strong, balanced framework of branches that will carry the tree for the rest of its life. By year 4, the structure should be set, and pruning then shifts to maintenance. Carry out formative cuts in mid–late summer (after harvest) in dry weather; avoid winter pruning on cherries.

Bush / open-centre (goblet)

Year 2: Select 3–5 well-spaced shoots from the maiden’s regrowth to form the main framework. These should radiate outward, not crossing or crowding each other. Remove any weak, inward, or vertical shoots. Shorten the selected branches by about a third, cutting to outward-facing buds.

Year 3: From each main branch, choose 1–2 strong laterals to build secondary branches. Again, keep them pointing outward to maintain an open centre. Shorten vigorous new growth by about a third. Remove any shoots growing into the centre.

Year 4: The goblet framework should now be established. Lightly shorten strong new shoots to encourage spur formation and remove any congested, weak, or inward growth.

By the end of year 4, the bush should have 3–5 main branches forming a balanced, open centre.

Half-standard

Year 2: Select 3–5 strong shoots arising from around 80–100 cm height to form the canopy framework. Remove any shoots below this height on the trunk to keep a clear stem. Shorten the selected branches by about a third, cutting to outward-facing buds.

Year 3: Build secondary branches as for the bush, choosing outward-pointing laterals from the main branches. Maintain the clear trunk by rubbing out any shoots forming lower down.

Year 4: Maintain and balance the canopy. Shorten strong new shoots by a third, thin congested growth, and keep the canopy open.

By the end of year 4, the half-standard should have a lifted canopy with 3–5 main arms, similar to a bush but on a taller trunk.

Fan-trained

Year 2: Tie in the two arms created from the maiden cut, keeping them angled at 35–45° to form the base of the fan. Select 2–4 additional strong shoots and tie them out on either side to extend the fan. Remove inward- or upward-pointing shoots. Shorten side shoots along the arms to 3–4 leaves in summer.

Year 3: Extend the fan by tying in more shoots evenly to fill the framework. Replace any weak or poorly placed arms with new growth. Summer-prune all side shoots along the arms to 3–4 leaves.

Year 4: Aim for a balanced fan with 6–8 well-spaced arms. Continue to tie in strong extensions and prune side shoots to 3–4 leaves. Remove congested or shaded growth.

By the end of year 4, the fan should cover its wall or fence space with an even spread of arms.

Pruning mature cherry trees (maintenance pruning)

Once a cherry tree has reached its shape (from about year 5 onwards), pruning changes from building the framework to maintaining it. The aim is to keep the tree healthy, balanced, and productive without forcing strong regrowth.

Key points for maintenance pruning:

Thin congested growth – Remove some of the shoots where branches crowd together. This keeps light and air moving through the canopy, which helps flower bud formation and reduces fungal disease.

Renew old spur wood – Cherries crop best on younger spurs. If branches are covered in tired, downward-hanging shoots carrying small fruit, cut some of them back to a younger side shoot or remove and let new growth replace them.